September 11, 2020 – Our fall term will be hybrid, but most students will participate on campus. We’re still not permitted to gather in groups larger than 50, so the opening of our academic year was an on-line ceremony. Per our tradition, the fall All College Meeting Moderator opens the ceremony. We had a handful of students welcome the community before I launched into my address, which — also per tradition — ends with a talk by an invited alumni. Here’s what I chose to say.

CONVOCATION 2020. Thanks everyone and welcome, once again, to Convocation at College of the Atlantic. This is the 49th opening of the academic year here at COA – next year, we’ll use Convocation to kick off the celebration that mark’s our 50th anniversary.

I’m so proud of and grateful for all the work we’ve done to get here today. I’m not sure I’ve ever been this excited to say hello to you, Eben though I can’t even see, you. Today “you” is a much larger, more dispersed group than is normal for us. You are students, staff, faculty, but also parents, trustees, alumni, and friends. You are on Zoom or Facebook and you aren’t in Gates; you are all over campus; you are across the street and up the hill at Summertime; out on Norris Avenue; in Portland, Maine, Portland, Oregon, Providence, or Portugal.

Although we’re separated by great distances and are communicating through horribly imperfect digital representations of each other, and, even when physically together, we’ll be separated by masks and six feet, I’ve never felt closer to all of you or to the beating heart of the institution.

In case you couldn’t tell, I’m not in Gates. I’m actually at my mother inlaws’ kitchen table in Atlanta, Georgia.

I spent the last two days on a road trip to get here – 1,341 miles, 21 hours, 12 states – to bring my daughter Maggie to college.

I had what I thought was a good talk nicely wrapped up before I left, but I decided to throw it all out and use the road trip as inspiration. Those mind-numbing nighttime miles, the ridiculous arguments over directions with Siri, the arguments with my girls over music, the high volume of sugar and salt and caffeine, the high volume of Cardi B and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon would be the elixir to beget some small but potent kernel of insight to begin the academic year.

That may have been a dangerous plan.

But the kernel I uncovered was the journey itself – today I very much want all of you, but especially the students, to consider the word, the idea, the act of peregrination. The pilgrimage. The sojourn. You are, we all are at the beginning, at the end, and in the middle of some many pilgrimages great and small. Your pilgrimages and mine, short and long in both space and time, are strands that we splice together to form a rope, our history.

I decided to focus on peregrinations somewhere between Farnhurst, Delaware and Bay View, Maryland. To help consider your own journeys in a new light and to help begin this process of splicing, I’ve got three journeys for you to mull.

One. The footsteps and canoe strokes of the Passamaquody people have made tracks across Mount Desert Island and the Dawnland of Downeast Maine for Millenia. Before any other peregrination of your own, consider theirs.

The Passamaquody is one nation of the five-nation Wabanaki Confederation. According to the Passamaquody, when the creators made the Earth they left it unfinished. They brought into being a person, named Koluskap, to finish the work they’d started. They also brought forth a sorceress named Poo-kin-skeh (sic, phonetic), who fell deeply in love with Koluskap, but who’s love was not reciprocated. Poo-kin-skeh became furious by this unrequited love and so stole off with Koluskap’s relatives, the woodchuck and the martin. And a great chase ensued across the Dawnland – an epic peregrination – where the footsteps of Koluskap chasing Pookinskeh created the landscape we inhabit today.

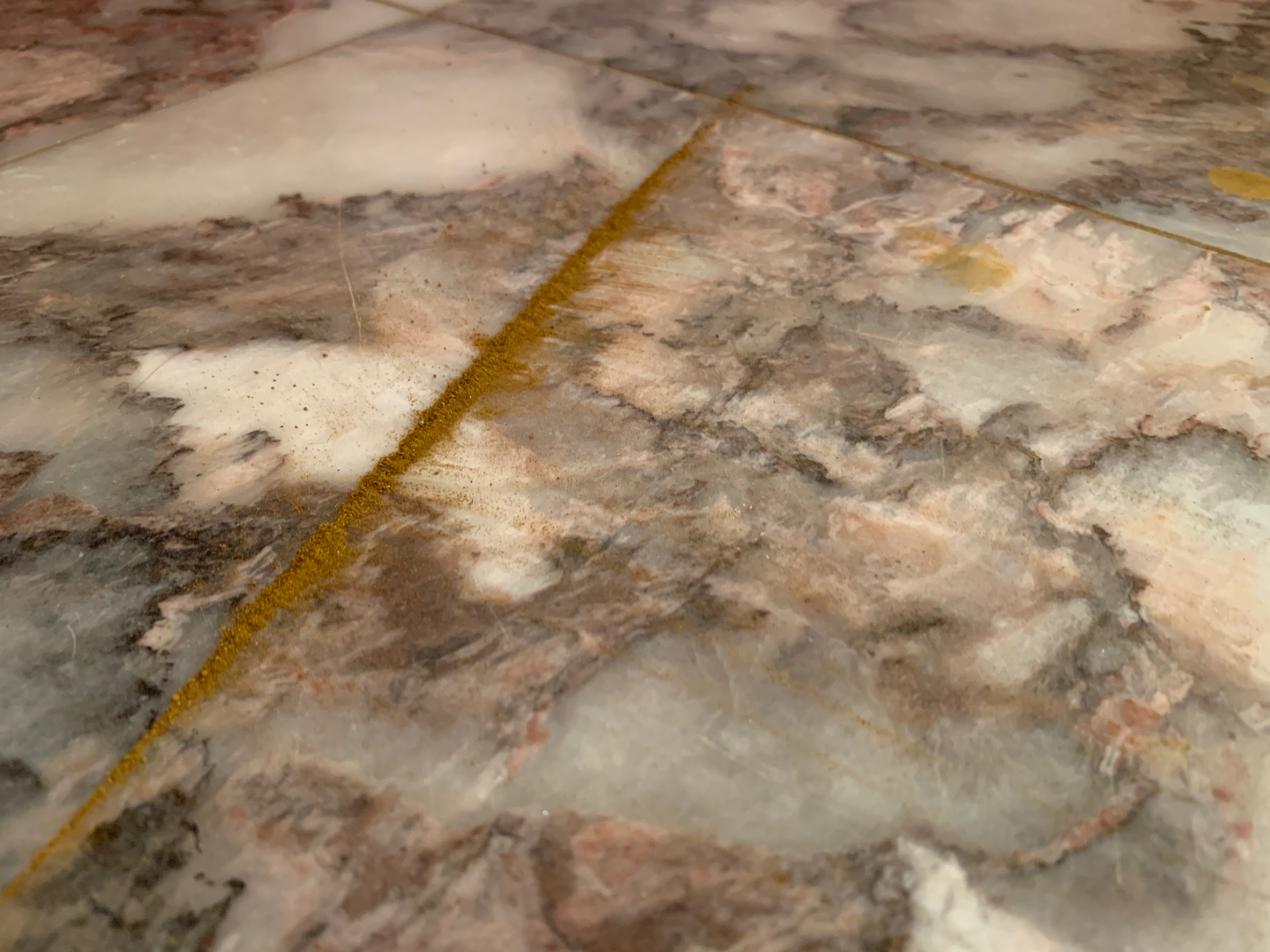

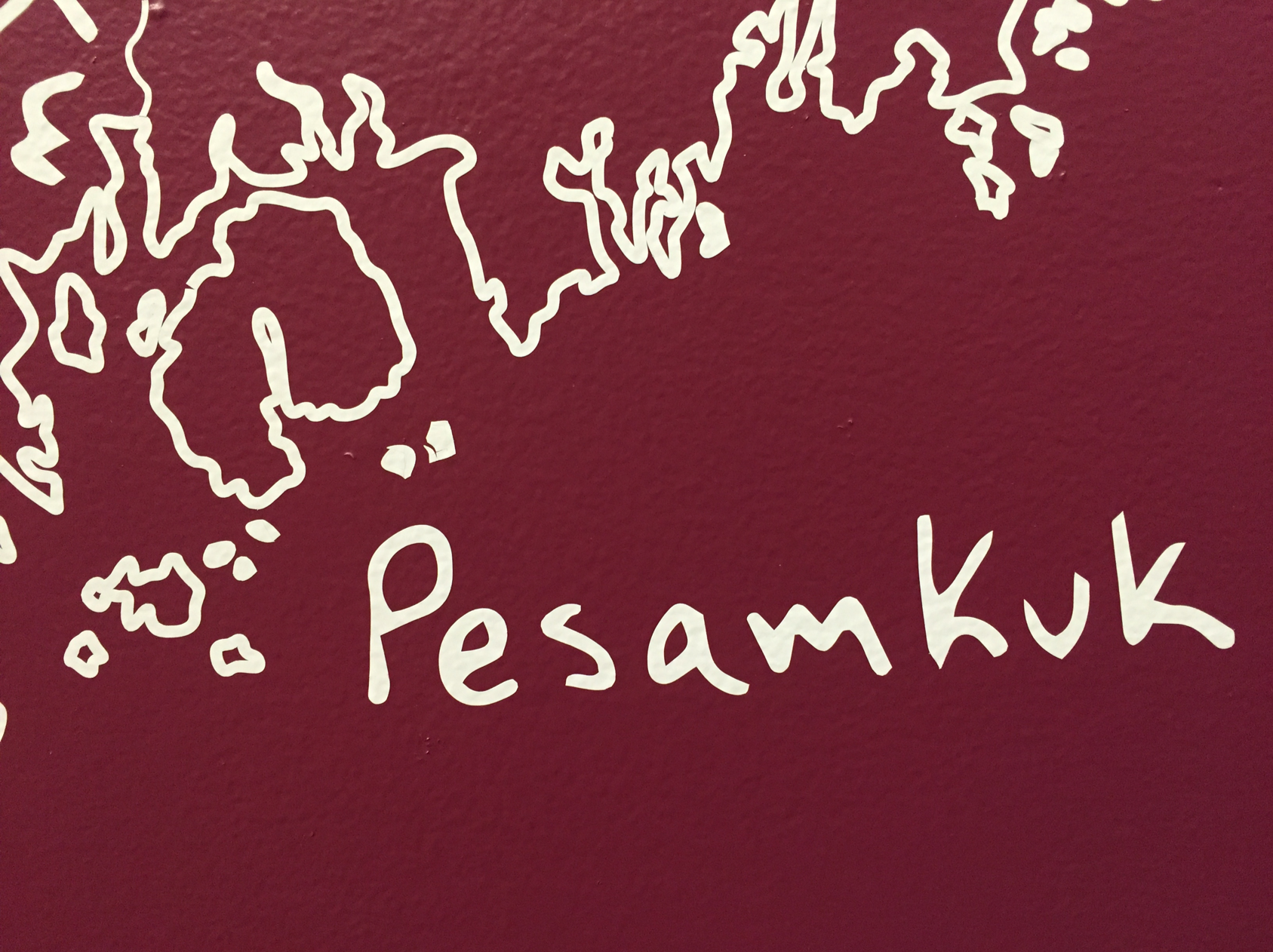

Koluskap finally caught Poo-kin-skeh, brother woodchuck, and nephew martin on a great island. That island is called Pesumkuk, which means the sandy hunting and spearing place; today, Pesumkuk is typically called by another name, Mt. Desert Island. Pesumkuk is our home and our context for many great physical, spiritual, and intellectual pilgrimages to come.

This pilgrimage story is a way I’d like to acknowledge the Wabanaki presence and history. But, honestly, it’s not enough to simply acknowledge. We must also recognize the continual violations of water and territorial rights and the defamation of sacred sites in the Wabanaki homeland. We have a collective responsibility to help address those issues, if called upon and as needed.

And, you know, the best way to prepare for giving that help is for all of you to come to know Pesumkuk, this island; know it intimately by laying your own songlines across the mountains and oceans with peregrination and pilgrimage, which brings me to my second story.

Two. Two weeks ago today, a remarkable human being, COA alumna Puranjot Kaur, attempted to swim around Pesumkuk – 44 miles, 24 hours, 58 degree water, no wetsuit.

I had the honor to help feed her on the journey from the cockpit of a kayak. It was one of the most amazing events, encounters, peregrinations I’ve ever been a part of. The athleticism and determination was one thing: I watched this woman vomit while treading water – let me say that again, vomit while treading water – she’d consumed who knows how much seawater in the waves brought on by a nasty, unexpected southeasterly wind. She then tried to put warm tea into her body – her body temperature at 86 degrees, she was shaking violently; yet she put her face back in the water to struggle against the incoming tide. I’ll admit, I have a soft spot for people pushing themselves physically – but I’m still amazed.

She didn’t make it. She swam 17 miles from Hadley Point to Otter Point before the team doctor correctly and emphatically called it. We managed to get Puranjot’s exhausted, extremely slippery body out of the water, onto COA’s boat the Osprey, to Seal Harbor, and to MDI Hospital. I cried like a little baby. In terms of expectations, she failed. In terms of a peregrination, it was a win on the most epic scale. I’ve never seen the MDI community come together with such gusto — they lined the island to catch a glimpse. Her support crew of 16 were ore than half COAers. She raised over $30,000 to fight food insecurity. Again — a success of epic scale.

I must have been somewhere near the huge Peach water tower in Gaffney, South Carolina before it hit me that it wasn’t really the what of Puranjot’s journey that was so amazing as much as the why. Hers was a journey of cause. Now not every walk in the woods needs to have such a profound why, but we as a COA community are bound together in part because we are so incredibly dedicated to affecting change on this planet – our lone footprints become footpaths when we hone in on a collective why, like Puranjot did in working to end food insecurity on Pesumkuk.

Three. One of the greatest peregrinations of the why variety that’s ever taken place – and my third and final story – was when Dr. Martin Luther King, John Lewis, and 2000 civil rights activists made the 54-mile journey from the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama to Montgomery in March of 1965. It was their third attempt. They weren’t beaten back by ocean waves and tides, but by State Trooper tear gas and billy clubs; but on March 21, 1965 they crossed the bridge and on March 24 those marchers arrived in Montgomery – their collective footfalls put down an amazing path, today known as the Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights Trail – and on August 6, 1965 the Voting Rights Act became law.

We as a COA community have the collective responsibility to add to those songlines from 55 years ago, to continue the march, to continue the splicing of our own threads, because clearly the work to end racism and discrimination is far from complete. Our institutional peregrinations this academic year must include the hard work of building an anti-racist, inclusive Human Ecology in our own minds, here on campus, on Pesumkuk, and among humanity writ large.

So that’s it – that’s my message. Consider the peregrination. But there’s one more thing. It may seem like a non sequitur and it is, in fact, from the first address that I claimed to have tossed away. Here it goes: get a notebook. That’s right, get a notebook. Bossy, perhaps. Please get a notebook.

Buy or make an actual, physical, collection of bound sheets of paper – carry it with you on your peregrinations. We must record these times. Your description of your experiences at COA will become a historical record of amazing times.

Write things in your notebook: your dreams; a newly learned word; a suggested reference provided by a faculty member; a poem; a piece of code; an outline of a research paper; your manifesto. Clarity in writing is clarity in thought. Authorship of well-constructed paragraphs gives you a new authority on ideas.

Draw things in your notebook. Doodle mindlessly, but also try and capture reality. Focus on leaves or stones or detritus on the forest floor, because the more you look, the more you see. Drawing is a tool to hone your attention.

Count things in your notebook. Count the number of eider ducks in a flotilla you see while walking the shores of Pesumkuk. Count the number of cars passing a point in a certain amount of time. Get familiar with the mean, median, and mode, but also with the wonderful tails bell curves.

Does that sound crazy? I hope not. I want all of you to consider the journey of this academic year as a sometimes sacred other times profane, a sometimes short sometimes long, a sometimes purposeless but other times purposeful pilgrimage – one that ties us together as individuals, as a community, and as humanity… and I want you to get a notebook, please.

***

Every year we invite a COA graduate to provide us with some of their perspective and this year I have the honor to introduce Dr. Amy Wesolowski, a graduate from the class of 2010. Amy is on the faculty of the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University. Before arriving at Hopkins, Amy was a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton and at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. She studies human mobility patterns and their relationship to infectious disease .. which seemed somewhat relevant, don’t you think? She was one of the first people I reached out to back in the spring when we were trying to outline an appropriate strategy for opening this year. An amazing resource to be able to lean on and an amazing person, please welcome Dr. Amy Wesolowski.